Excited? Oh, no. I'm way, way beyond excited. In a few days, I'll take in the Rose Parade and the Rose Bowl. I feel like one of those girls on the old newsreels who screamed at the Beatles as they arrived in America. It's just pure, unadulterated excitement. It's bliss. Win or lose, I'm going to love this.

TCU is going to the Rose Bowl. I'm off to sprinkle rock salt where hell froze over.

GO FROGS!

Wednesday, December 29, 2010

Sunday, December 12, 2010

Pony Excess

For the most part, I liked Pony Excess, the ESPN 30 for 30 film about the SMU football program in the early '80s. There's just one gripe I'd like to get out of the way right off the bat.

A couple of times, when one of the figures in the documentary (it might have been Dallas radio host Norm Hitzges) mentioned that TCU also got hit with probation in the '80s, the video cut to clips of former TCU coach Jim Wacker. That upset me, and here's why.

It's true that the NCAA handed TCU an extremely harsh penalty in 1985 while Wacker was coach. But it wasn't the late Coach Wacker who did the cheating. In fact, Wacker, an honest and upstanding man, turned TCU in voluntarily--something that had never happened before--as soon as he found out about payments from boosters. He had not been part of the cheating, although his predecessor, who was a huge loser, very well might have been. Wacker also dismissed 11 players from the team in 1985, including star running back Kenneth Davis, before the NCAA ever made it to Fort Worth.

Wacker hoped that his honesty and transparency would lead to leniency from the NCAA, but it didn't. TCU got the "walking" (or "living") death penalty two years before the NCAA shut SMU down. The sanctions effectively paralyzed our program for a decade. I'm sure it was an innocent piece of b-roll, but I found it borderline offensive that Wacker's image was associated with TCU cheating. I'm probably the only person who noticed that, though.

One of the very prescient points the documentary--which was directed by an SMU grad whose dad is a professor at SMU--made was that everybody in the old Southwest Conference was cheating in the 1980s. (I was surprised to hear a few ex-SMU players say that Rice had approached them with "incentives"--I was always under the impression that Rice was the only clean program in the SWC during that era. Apparently everybody was trying to buy talent, even little Rice.)

In a documentary about SMU, it might not have been appropriate to take this tangent, but it upset me a little bit that nobody mentioned the fact that SMU got hit with the death penalty while Texas A&M, eligible for the death penalty for multiple violations stretching over a decade, got a series of slaps on the wrist and mainly continued to run a successful program. A nice naming and shaming of A&M would have been appropriate, but that's not what the film was about.

For a documentary made by an SMU alumnus and confessed SMU football fan, the film did plenty of naming and shaming of former SMU coaches, players and administrators. Craig James, who works for ESPN, almost assuredly took payments but acts like an innocent in the film--which makes him come off as either a liar or a total rube for not getting in on the cash. His backfield partner, Eric Dickerson, revealed a lot about what other schools (notably A&M) gave him but stopped short of talking about SMU's largess. He didn't say that SMU didn't give him anything (who would even begin to believe that?); he just said that he didn't want to talk about it. Fair enough, I guess.

Former Texas governor Bill Clements comes off looking like the two-faced idiot he was, but the coaches and administrators who were at SMU in the late '70s and early '80s--including former SMU coach Ron Meyer, who did an interview for the film--actually manage to come off looking worse. The boosters, the real money behind the illegal payments to players that were so rampant for years, are who they are--a bunch of rich, old Texans who wanted their team to win. They don't try to be anything else in the movie, and several of them did sit for interviews.

It's Meyer and SMU's braintrust of the era--most of whom did not sit for interviews--who really look sleazy. Meyer, who never had a lot of scruples, anyway, doesn't seem too ashamed about anything. The other SMU admin honchos, mainly shown in extremely embarrassing and revealing TV interviews from the '80s, have all the sideways glances and slack-jawed looks of the very most busted victims of 60 Minutes. And, as the movie points out, they were just so stupid. One official in the athletic department sent money to a recruit in an envelope embossed with the SMU seal and his own handwriting on the letter inside. Really?

One of the reasons I watched this movie was because I wanted to relive some of the good days of the SWC, back before all the cheating came to light and the conference imploded. I remember the whole SMU saga very well. As a small kid--prior to 1983, when Wacker arrived at TCU--I was an SMU fan. Who wouldn't have been? The Ponies were awesome to watch; they were the underdogs who were finally having their day against the giants of the SWC, and they were located right in Dallas, just 30 miles or so from my hometown. They even had cool nicknames--Dickerson and James (sometimes known as Dickerjames) were the Pony Express, and the whole SMU fervor was called Mustang Mania. Mustang Mania? That's great!

What I realized as the movie went on was just how depressing college football got in the 1980s in Texas. I didn't lose my football innocence with SMU. I lost it before that, as a newby TCU fan, when the Frogs got smacked with probation when I was 11 years old. I was bitter for years--still am, really--about how the NCAA treated TCU compared to what it did (or didn't do) to UT and especially A&M. I still watched college football religiously, but TCU's plight soured me on the sport in a way I'm not completely sure I've totally recovered from.

From there, SMU went down, A&M's dirty program rose and I entered my junior high years, which would have been miserable enough but were made all that much worse by the fact that my hometown was saturated with arrogant, obnoxious A&M fans. As I watched the film tonight, I remembered how miserable the years from 1986-1990 or so were for me (which is not a comment on my family, just on my stage of life) and how college football, my passion, actually made them worse. It's a wonder, honestly, that I'm a fan to this day. Many TCU alumni didn't bother to stay on the mostly empty bandwagon. Many SMU alumni didn't, either--and who can blame them? In 1987 and '88, they had no football team. It gets no worse than that.

SMU did deserve the death penalty. It did. SMU was arrogant and blatant in its repeated cheating, and its administrators knew to the highest level (and beyond) what was going on and still lied repeatedly about what they were doing. All of SMU's success from 1980-1984 came from cheating. The legacy of those teams, so successful and so much fun to watch, remains tarnished forever. SMU is still the most penalized program ever, although the one that comes behind it is Texas A&M.

And that's what's not fair and why I've had a soft spot for SMU since 1989. (I'm glad to see the program getting back on its feet now--really.) Lots of programs have deserved the death penalty--A&M, Alabama, Miami for heaven's sake--but only little SMU, a private school with a small fan base, got it. I remember watching SMU win the Miracle on Mockingbird Lane, a comeback win over Connecticut in just the program's second game back after the death penalty. A little quarterback named Mike Romo led the Ponies to a stunning fourth-quarter comeback. Around him was a rag-tag bunch of guys, not recruited by anybody, undersized, slow and unable to really compete with anybody...except UConn. I was glad SMU won that game, and I still think of it as a pleasant sports memory. I'm no SMU fan, though. The Mustangs are still TCU's rivals, and I relish the chance to beat them year after year.

Of course, SMU's downfall was a big domino in the ultimate demise of the SWC, the very definition of college football for me in my childhood. I've never gotten over the breakup of the SWC. Sure, TCU has a much, much better program now than we did in the last couple of decades of the SWC, but there was nothing better than the rivalries that went with that historic old conference. Of course, there was nothing worse than losing those games, which we usually did. Still, as we've improved over the years and bounced around the country from conference to conference, I've wished that we could have had the success we're having now back in the '80s, when it would have meant so much to me as a kid obsessed with college football and filled with rage at programs like Texas and A&M.

But all's well that ends well, I suppose. Maybe that'll be the case for SMU fans someday (and maybe it is already, with a second straight bowl berth)--Lord knows they've suffered, and those who have remained supporters of the program deserve some success. For TCU fans, with a No. 3 ranking and a first-ever trip to the Rose Bowl on the way, this is probably the best things have ever been. Oh, sure, we were arguably better in the '30s and maybe even in the '50s, but that's quite literally ancient history in college football terms. From wondering 12 years ago whether I'd ever see TCU win a bowl game to planning a trip to Pasadena last week (I'll see you there...), this ride has been incredible. OK, so it didn't happen against Arkansas and Texas and A&M, but it is happening. And for that, I'm thankful. Go Frogs.

A couple of times, when one of the figures in the documentary (it might have been Dallas radio host Norm Hitzges) mentioned that TCU also got hit with probation in the '80s, the video cut to clips of former TCU coach Jim Wacker. That upset me, and here's why.

It's true that the NCAA handed TCU an extremely harsh penalty in 1985 while Wacker was coach. But it wasn't the late Coach Wacker who did the cheating. In fact, Wacker, an honest and upstanding man, turned TCU in voluntarily--something that had never happened before--as soon as he found out about payments from boosters. He had not been part of the cheating, although his predecessor, who was a huge loser, very well might have been. Wacker also dismissed 11 players from the team in 1985, including star running back Kenneth Davis, before the NCAA ever made it to Fort Worth.

Wacker hoped that his honesty and transparency would lead to leniency from the NCAA, but it didn't. TCU got the "walking" (or "living") death penalty two years before the NCAA shut SMU down. The sanctions effectively paralyzed our program for a decade. I'm sure it was an innocent piece of b-roll, but I found it borderline offensive that Wacker's image was associated with TCU cheating. I'm probably the only person who noticed that, though.

One of the very prescient points the documentary--which was directed by an SMU grad whose dad is a professor at SMU--made was that everybody in the old Southwest Conference was cheating in the 1980s. (I was surprised to hear a few ex-SMU players say that Rice had approached them with "incentives"--I was always under the impression that Rice was the only clean program in the SWC during that era. Apparently everybody was trying to buy talent, even little Rice.)

In a documentary about SMU, it might not have been appropriate to take this tangent, but it upset me a little bit that nobody mentioned the fact that SMU got hit with the death penalty while Texas A&M, eligible for the death penalty for multiple violations stretching over a decade, got a series of slaps on the wrist and mainly continued to run a successful program. A nice naming and shaming of A&M would have been appropriate, but that's not what the film was about.

For a documentary made by an SMU alumnus and confessed SMU football fan, the film did plenty of naming and shaming of former SMU coaches, players and administrators. Craig James, who works for ESPN, almost assuredly took payments but acts like an innocent in the film--which makes him come off as either a liar or a total rube for not getting in on the cash. His backfield partner, Eric Dickerson, revealed a lot about what other schools (notably A&M) gave him but stopped short of talking about SMU's largess. He didn't say that SMU didn't give him anything (who would even begin to believe that?); he just said that he didn't want to talk about it. Fair enough, I guess.

Former Texas governor Bill Clements comes off looking like the two-faced idiot he was, but the coaches and administrators who were at SMU in the late '70s and early '80s--including former SMU coach Ron Meyer, who did an interview for the film--actually manage to come off looking worse. The boosters, the real money behind the illegal payments to players that were so rampant for years, are who they are--a bunch of rich, old Texans who wanted their team to win. They don't try to be anything else in the movie, and several of them did sit for interviews.

It's Meyer and SMU's braintrust of the era--most of whom did not sit for interviews--who really look sleazy. Meyer, who never had a lot of scruples, anyway, doesn't seem too ashamed about anything. The other SMU admin honchos, mainly shown in extremely embarrassing and revealing TV interviews from the '80s, have all the sideways glances and slack-jawed looks of the very most busted victims of 60 Minutes. And, as the movie points out, they were just so stupid. One official in the athletic department sent money to a recruit in an envelope embossed with the SMU seal and his own handwriting on the letter inside. Really?

One of the reasons I watched this movie was because I wanted to relive some of the good days of the SWC, back before all the cheating came to light and the conference imploded. I remember the whole SMU saga very well. As a small kid--prior to 1983, when Wacker arrived at TCU--I was an SMU fan. Who wouldn't have been? The Ponies were awesome to watch; they were the underdogs who were finally having their day against the giants of the SWC, and they were located right in Dallas, just 30 miles or so from my hometown. They even had cool nicknames--Dickerson and James (sometimes known as Dickerjames) were the Pony Express, and the whole SMU fervor was called Mustang Mania. Mustang Mania? That's great!

What I realized as the movie went on was just how depressing college football got in the 1980s in Texas. I didn't lose my football innocence with SMU. I lost it before that, as a newby TCU fan, when the Frogs got smacked with probation when I was 11 years old. I was bitter for years--still am, really--about how the NCAA treated TCU compared to what it did (or didn't do) to UT and especially A&M. I still watched college football religiously, but TCU's plight soured me on the sport in a way I'm not completely sure I've totally recovered from.

From there, SMU went down, A&M's dirty program rose and I entered my junior high years, which would have been miserable enough but were made all that much worse by the fact that my hometown was saturated with arrogant, obnoxious A&M fans. As I watched the film tonight, I remembered how miserable the years from 1986-1990 or so were for me (which is not a comment on my family, just on my stage of life) and how college football, my passion, actually made them worse. It's a wonder, honestly, that I'm a fan to this day. Many TCU alumni didn't bother to stay on the mostly empty bandwagon. Many SMU alumni didn't, either--and who can blame them? In 1987 and '88, they had no football team. It gets no worse than that.

SMU did deserve the death penalty. It did. SMU was arrogant and blatant in its repeated cheating, and its administrators knew to the highest level (and beyond) what was going on and still lied repeatedly about what they were doing. All of SMU's success from 1980-1984 came from cheating. The legacy of those teams, so successful and so much fun to watch, remains tarnished forever. SMU is still the most penalized program ever, although the one that comes behind it is Texas A&M.

And that's what's not fair and why I've had a soft spot for SMU since 1989. (I'm glad to see the program getting back on its feet now--really.) Lots of programs have deserved the death penalty--A&M, Alabama, Miami for heaven's sake--but only little SMU, a private school with a small fan base, got it. I remember watching SMU win the Miracle on Mockingbird Lane, a comeback win over Connecticut in just the program's second game back after the death penalty. A little quarterback named Mike Romo led the Ponies to a stunning fourth-quarter comeback. Around him was a rag-tag bunch of guys, not recruited by anybody, undersized, slow and unable to really compete with anybody...except UConn. I was glad SMU won that game, and I still think of it as a pleasant sports memory. I'm no SMU fan, though. The Mustangs are still TCU's rivals, and I relish the chance to beat them year after year.

Of course, SMU's downfall was a big domino in the ultimate demise of the SWC, the very definition of college football for me in my childhood. I've never gotten over the breakup of the SWC. Sure, TCU has a much, much better program now than we did in the last couple of decades of the SWC, but there was nothing better than the rivalries that went with that historic old conference. Of course, there was nothing worse than losing those games, which we usually did. Still, as we've improved over the years and bounced around the country from conference to conference, I've wished that we could have had the success we're having now back in the '80s, when it would have meant so much to me as a kid obsessed with college football and filled with rage at programs like Texas and A&M.

But all's well that ends well, I suppose. Maybe that'll be the case for SMU fans someday (and maybe it is already, with a second straight bowl berth)--Lord knows they've suffered, and those who have remained supporters of the program deserve some success. For TCU fans, with a No. 3 ranking and a first-ever trip to the Rose Bowl on the way, this is probably the best things have ever been. Oh, sure, we were arguably better in the '30s and maybe even in the '50s, but that's quite literally ancient history in college football terms. From wondering 12 years ago whether I'd ever see TCU win a bowl game to planning a trip to Pasadena last week (I'll see you there...), this ride has been incredible. OK, so it didn't happen against Arkansas and Texas and A&M, but it is happening. And for that, I'm thankful. Go Frogs.

Tuesday, December 7, 2010

The Party's Over

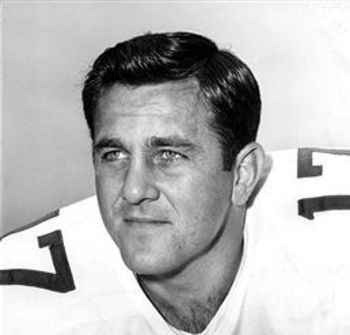

There will never be another Dandy Don Meredith. That much we know. Never the greatest quarterback for the Dallas Cowboys, he was nevertheless a very good one and an extremely tough one.

Long-time Cowboy fans like my dad probably remember the mid-'60s Cotton Bowl years as the best time to watch the team. Sure, Tom Landry's early teams couldn't get past the Packers. They lost heart-breakers in the playoffs. Meredith screwed up at the ends of big ballgames. Fans booed; sportswriters bristled. Roger Staubach would come along within a few years and make everything OK.

But real fans always have an affinity for those early teams that struggled, for the predecessors to the greats. Native New Englanders still talk with some nostalgia about Steve Grogan and the '70s Pats, about how Sugar Bear Hamilton was innocent and how the best New England team to come along prior to 2001 got robbed. Pat Patriot and the old red uniforms are still favorites around here.

As a TCU football fan, I'll forever be a Wacker Backer. I remember with fondness our rare victories in the '80s and early '90s and even some of our close losses. Stephen Shipley's last-second touchdown catch to beat Houston in 1991, in Coach Jim Wacker's last home game, remains one of my favorite sports moments. Names like Falanda Newton, Tony Jeffery and Matt Vogler are still special to me.

The championships help, of course. It's easy to remember Dandy Don now that Staubach and Troy Aikman have come and gone. Tom Brady makes the memories of Grogan seem a bit sweeter. Andy Dalton adds to Matt Vogler's nostalgic legacy. Do Cleveland fans look back with misty eyes on, say, Brian Sipe? Probably not. Success makes almost everything that preceded it seem sweeter.

Back to Dandy Don. He's one of those athletes who just predated my time, having retired a few years before I was born. And yet I feel as though I knew him, and not just because I did know him from his Monday Night Football years. He was a Dallas guy, a real one, an SMU All-American and Cowboy quarterback. He was quite literally the first Dallas Cowboy. In terms of his near misses in Dallas and lack of championship success, he was sort of my dad's Danny White, except that nobody came before Meredith in Dallas and that Dandy Don was a heck of a lot more fun than Dull Danny.

When I was a kid, Monday Night Football was still a huge event. It was still a cultural touchstone. Monday night games meant a lot--they were enormous for the cities and franchises involved, and they produced memories as lasting as many, if not most, of those that came from playoff games and Super Bowls. Howard Cosell--a television great in his own right, but one famously different from Meredith--Frank Gifford and Dandy Don made NFL football. They really did make it. No longer was the NFL a staid Sunday-afternoon fall pastime. It was cool. It was edgy. It was fun.

All of that's gone, of course. The 24-hour news cycle and the Web have swallowed the old notion of an "event," particularly one that happened every week from September through December. TV sports announcers try way too hard. Some try to be clever; others try to be controversial or bombastic, and still others try to be smarter than everybody else. Almost all of them fail. And with the NFL on five nights a week now, there are too many games and not enough good commentators.

The era of Monday Night Football ended almost 30 years ago. Don Meredith rode off into the sunset not long afterward. But with his passing, we should celebrate what he meant to Dallas sports and to American culture. No matter how badly he was hurt, no matter how much fans resented him, no matter how much flack he took from the press, he kept his cool. He didn't always win, but he never let his detractors get his goat. There's something very admirable about that. And very rare these days.

Beyond that, as an all-around fun guy, as a '70s icon, it was hard to beat Dandy Don. His decade on Monday Night Football was a high point for American entertainment and perhaps the absolute peak of the NFL as theater. But it's all over now. Meredith's days in the spotlight are long gone, and so is he. I'll miss him, not as a former fan but as someone who appreciates what he represented to a generation of football fans and to a young kid from Texas who used to beg his dad to let him stay up and watch the games on Monday nights.

The party has been over for a while, but now it's time to turn out the lights on the life of the great Don Meredith. Unfortunately, tomorrow will not start the same old thing again.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)